Borussia Mönchengladbach’s come-from-behind win against Bayern Munich was a statement victory that could just revitalise their league campaign. Gladbach fans would have been forgiven for feeling a sense of resignation when they fell two goals behind in a six minute first-half spell against the best team in Europe. But the unlucky way in which they fell behind shouldn’t distract from what was a very intelligent – and slightly wonky – tactical set-up, which targeted Bayern’s weakness on their right-hand side and resulted in a rousing Gladbach comeback.

The system focussed around two key individuals. There was naturally a lot of attention given to the absence of Marcus Thuram and Alassane Pléa, and when Bayern raced ahead, it was hard to see a way back for Die Fohlen without that duo. But it was another pair who defined this game for Gladbach. Jonas Hofmann and Denis Zakaria had not started a game together this season before this match, but it was the inclusion of both in the starting eleven for the first time which allowed Gladbach to play an asymmetric – and highly unorthodox – system, which paid off brilliantly.

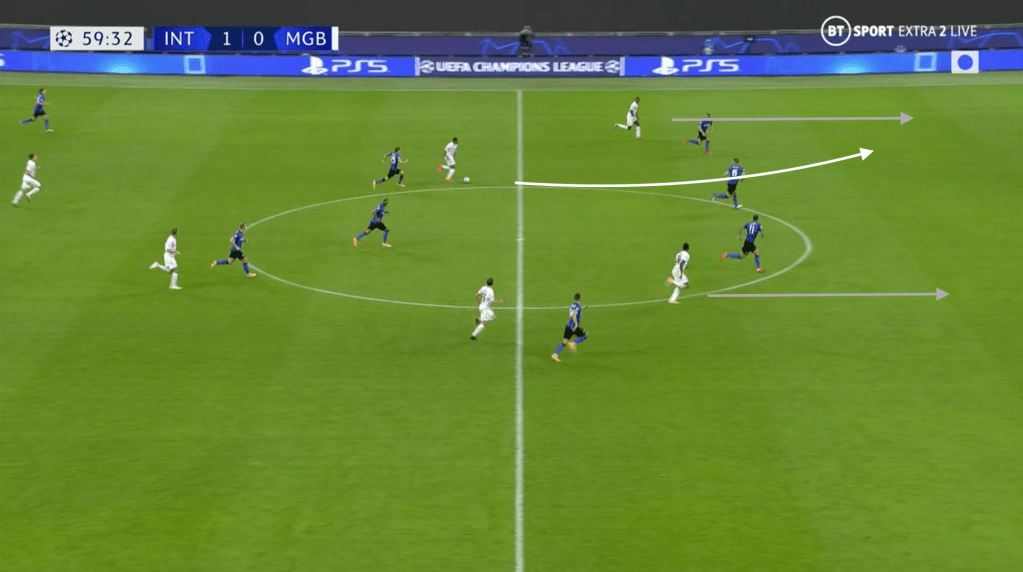

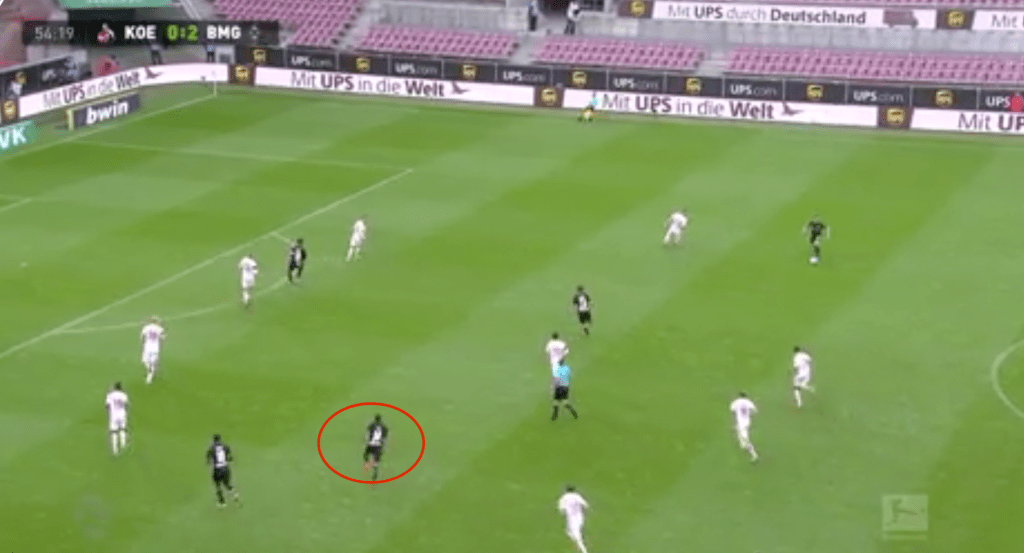

It sometimes looked like a 4-4-2. It sometimes looked like a 4-3-3. What was for sure was that Hofmann was on the left, and Zakaria was on the right. While Hofmann would push up against the Bayern backline, both when they were in possession to lead a press, and also to get involved in attacks, Zakaria was much more conservative, usually tucking in level with the central midfield pairing of Florian Neuhaus and Christoph Kramer.

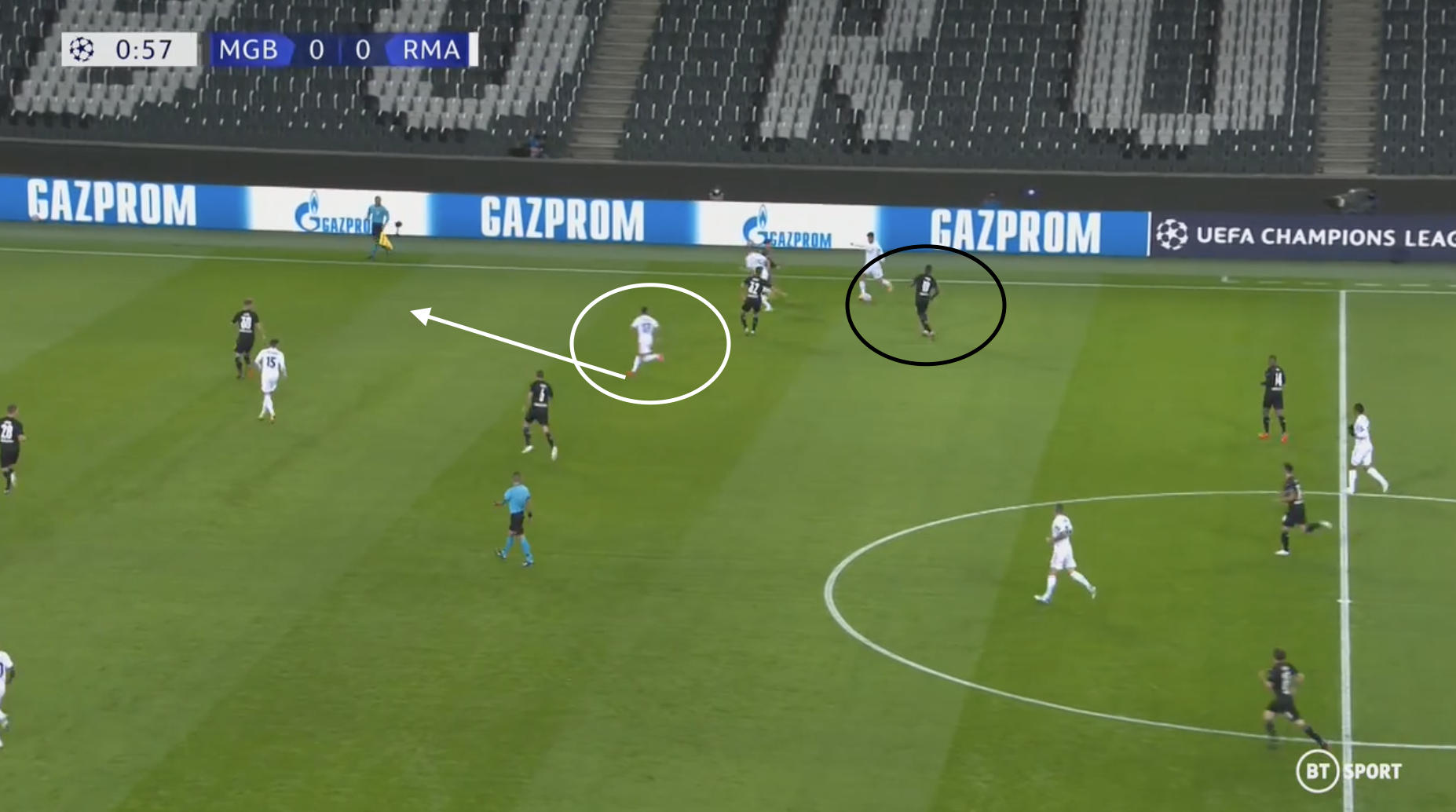

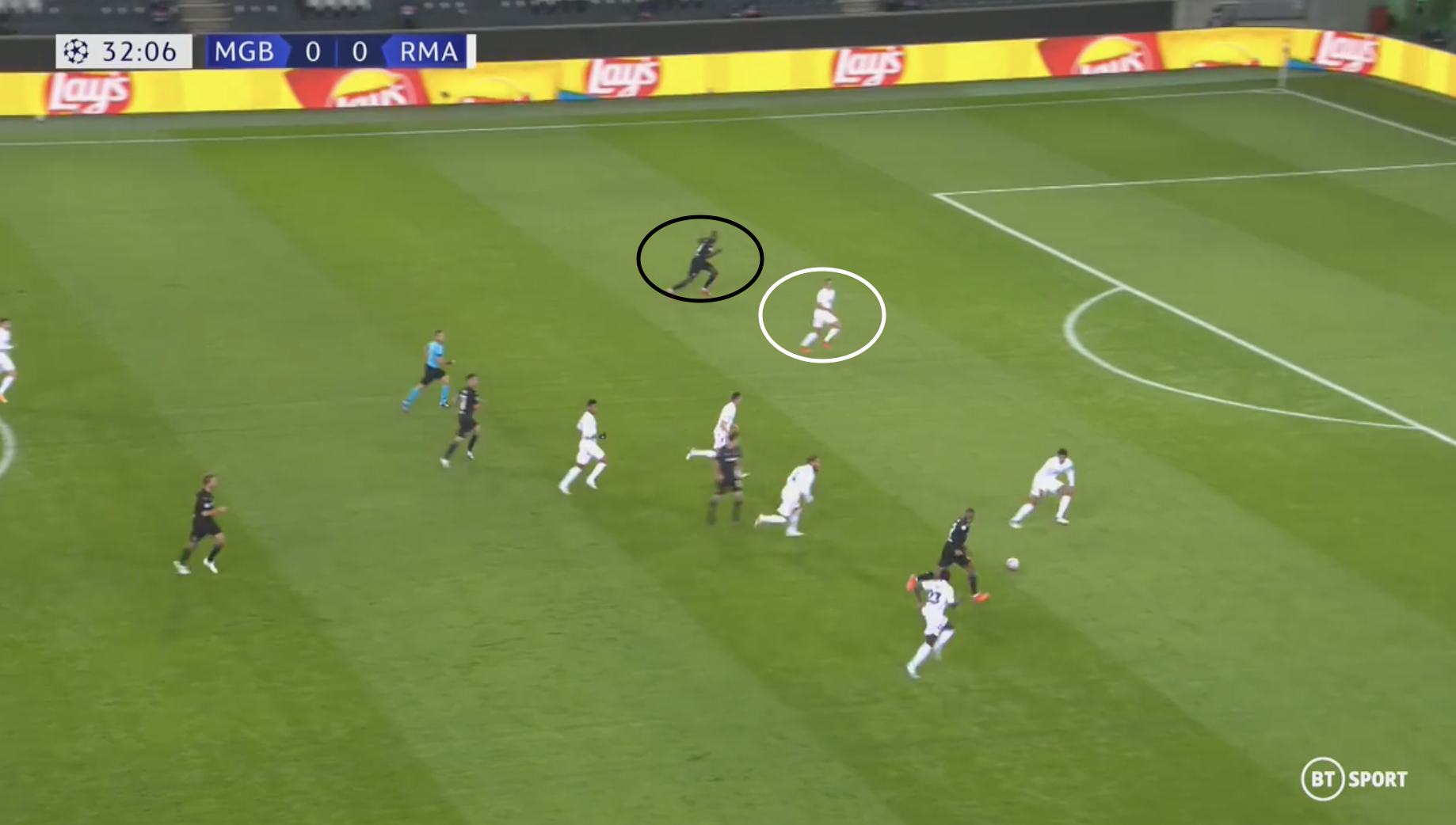

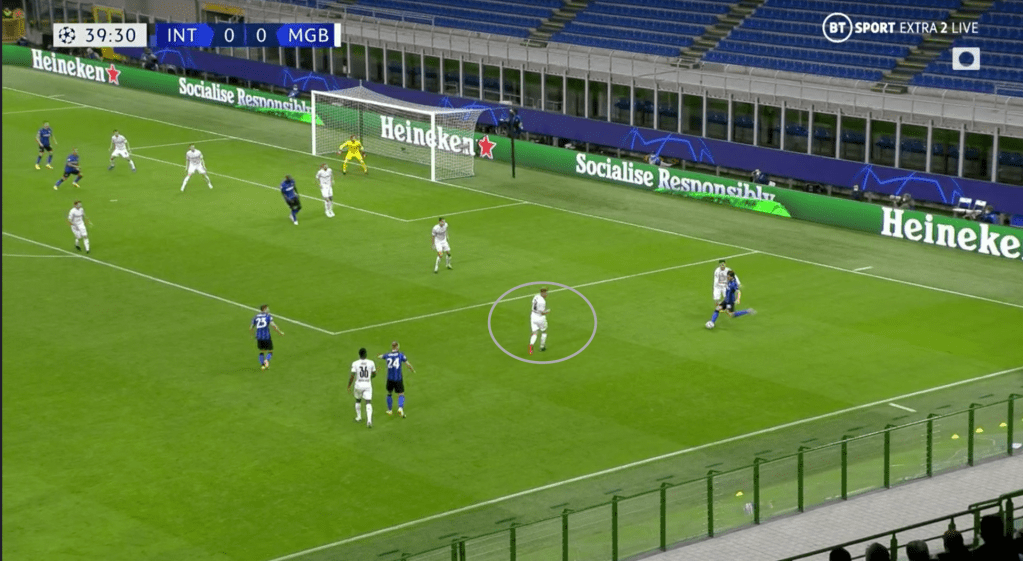

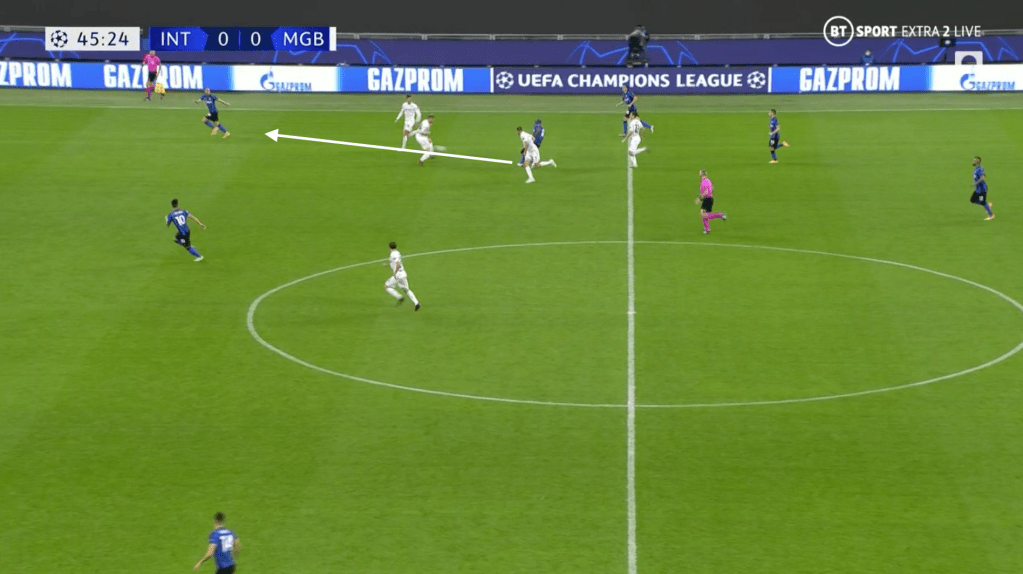

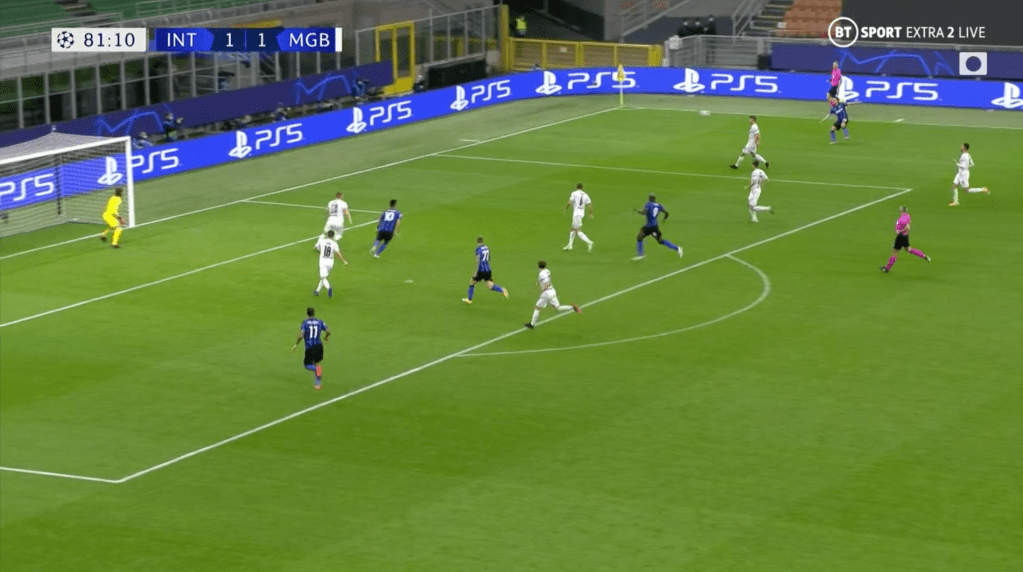

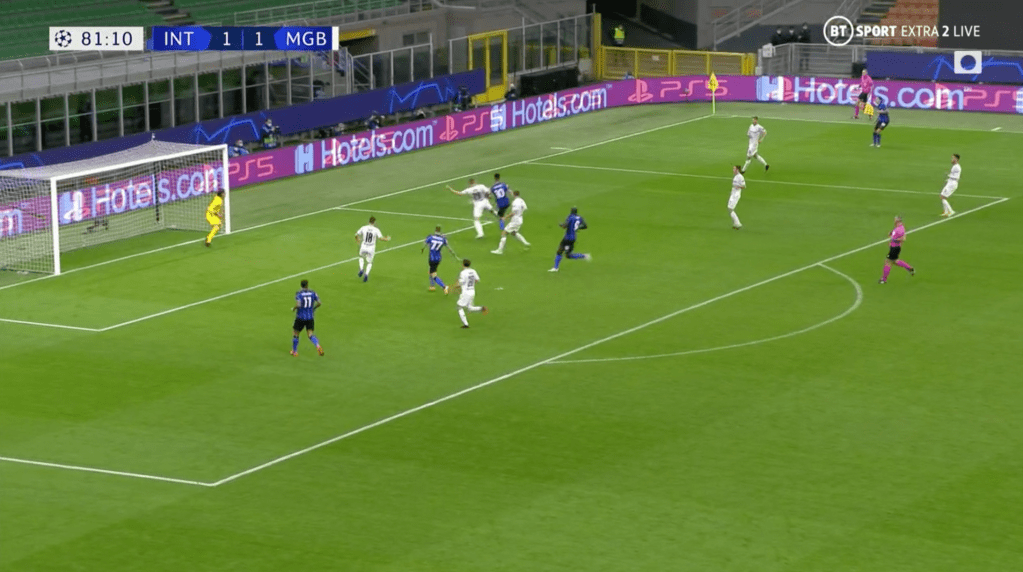

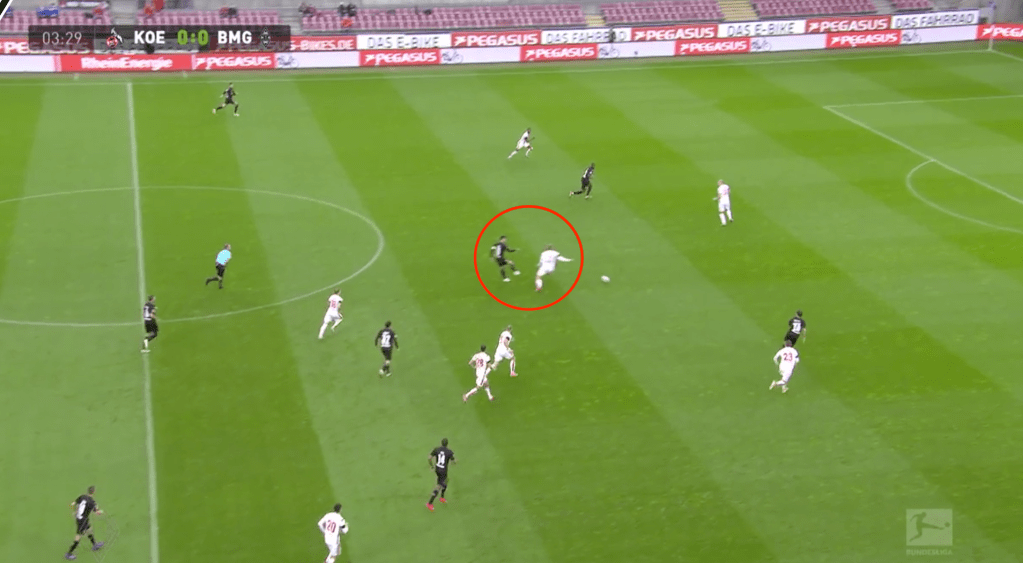

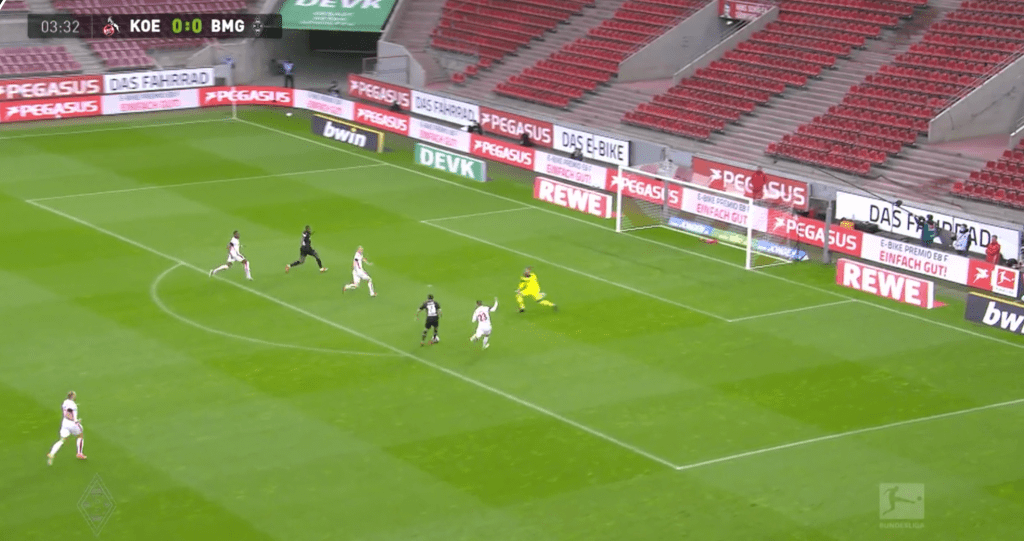

This, within the first minute, shows the setup well.

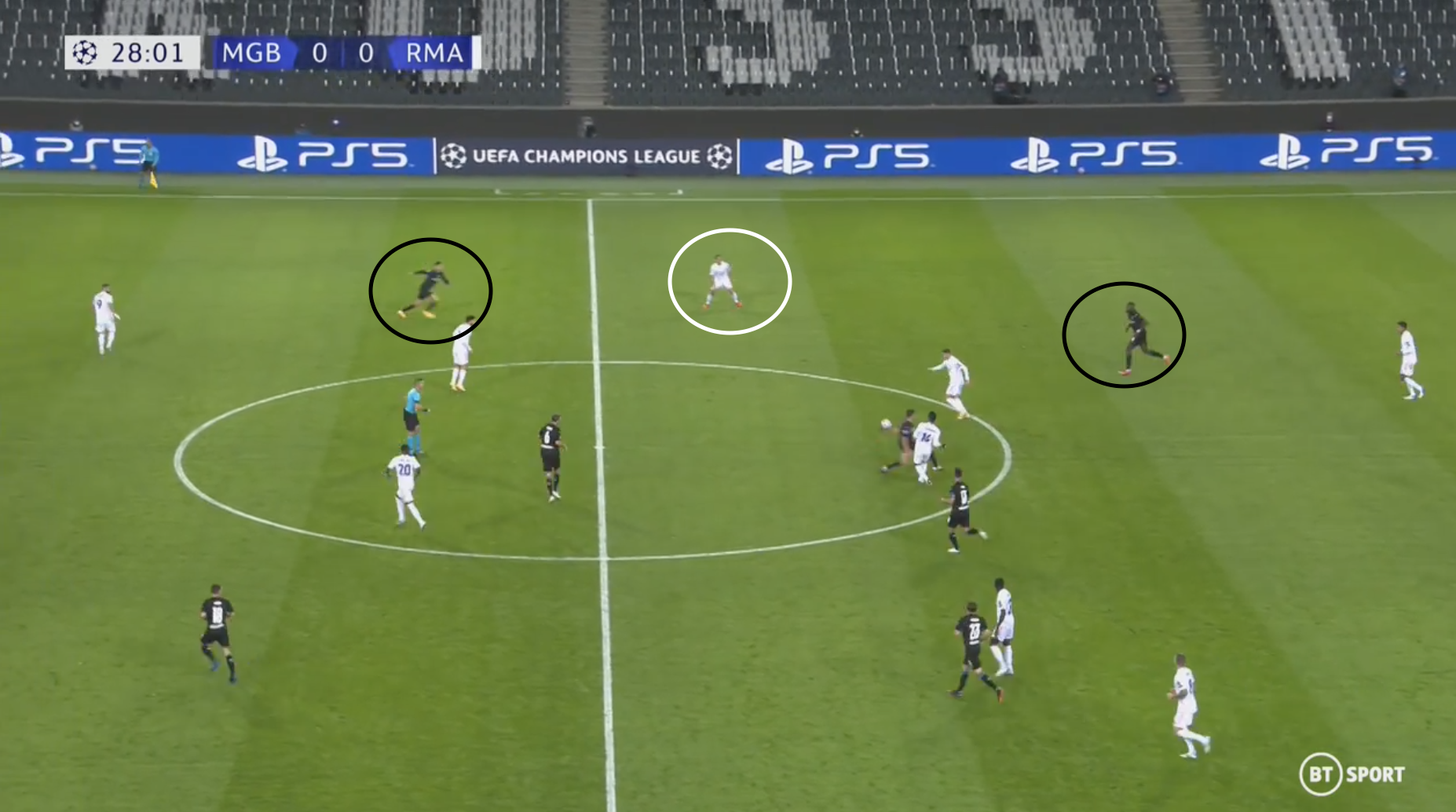

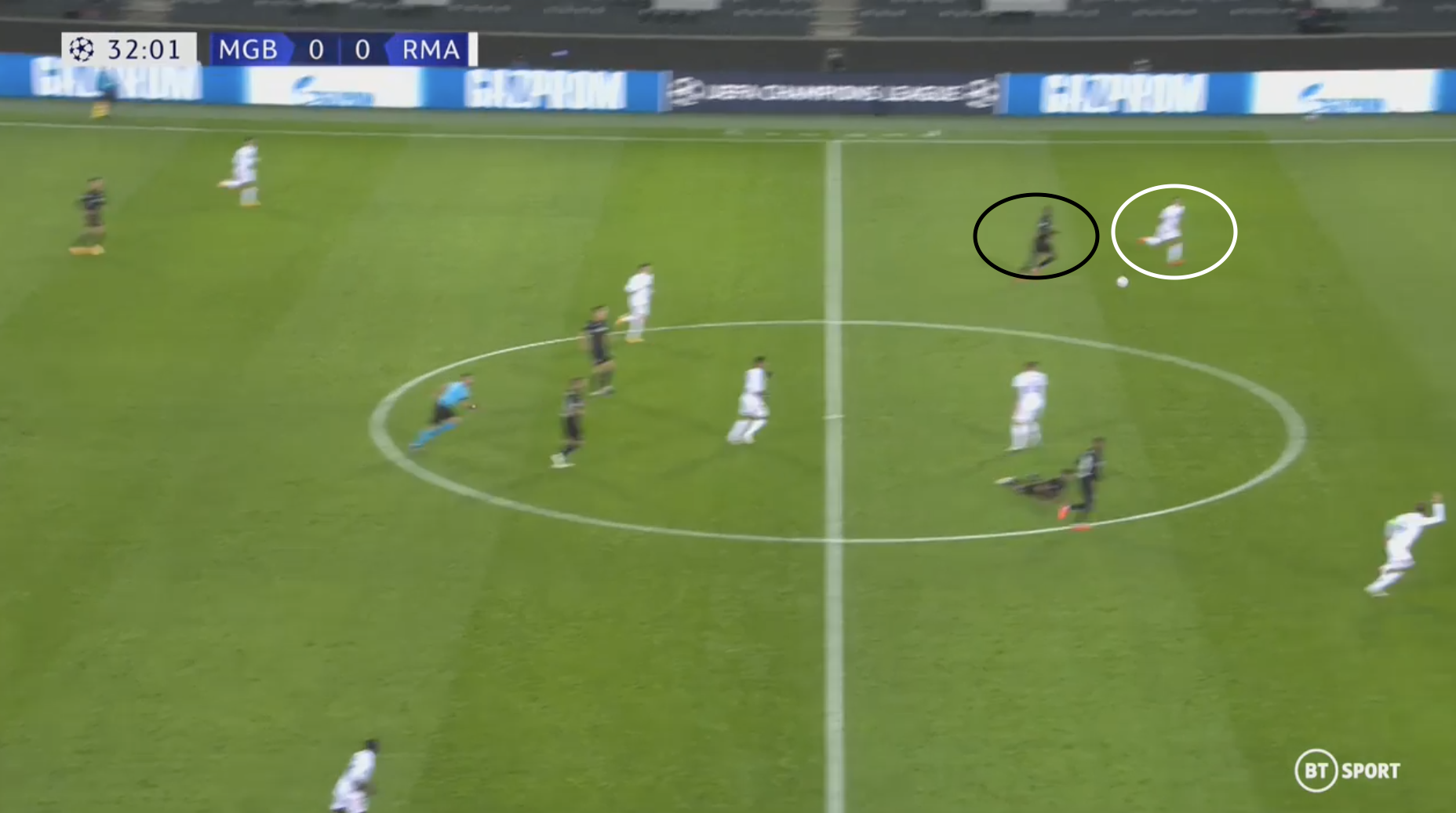

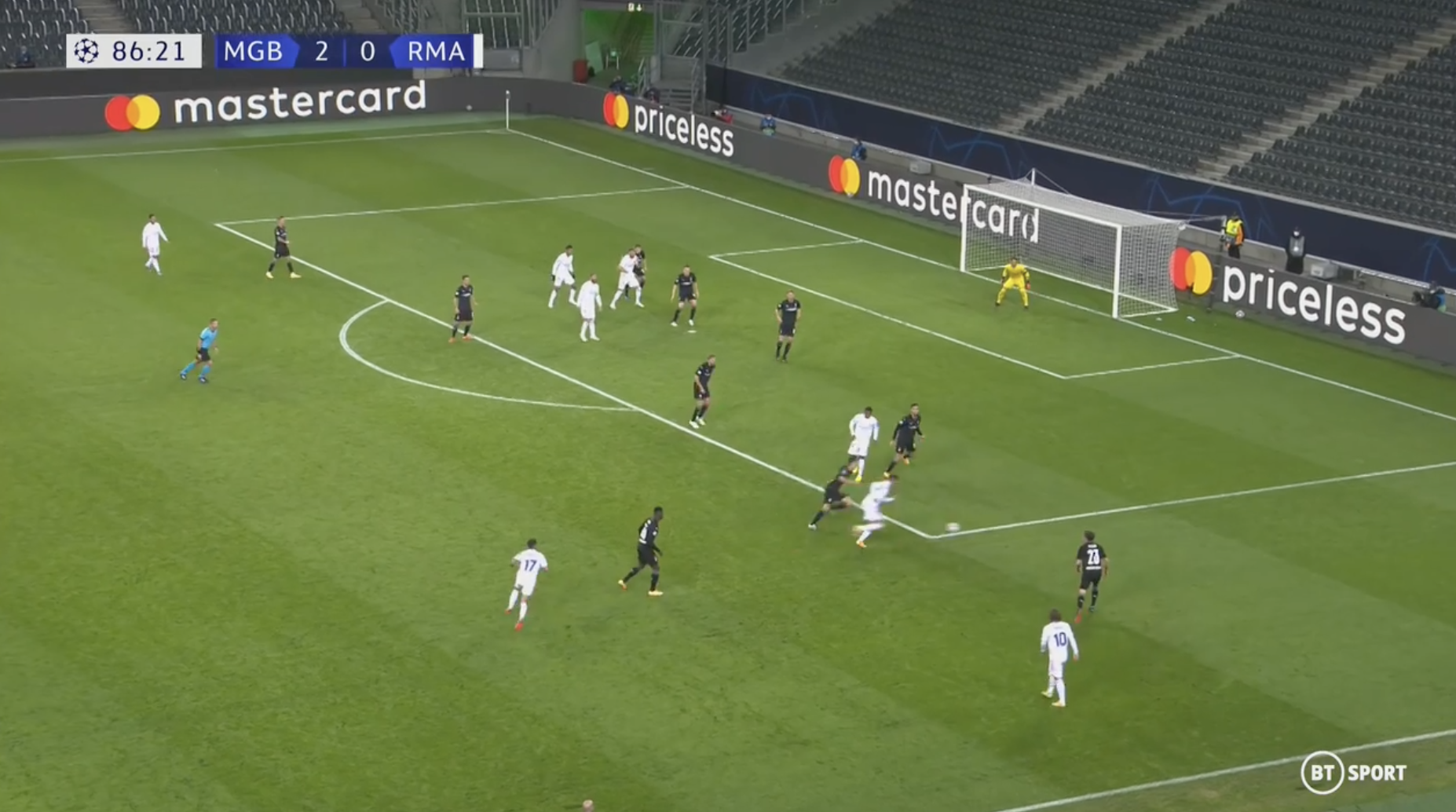

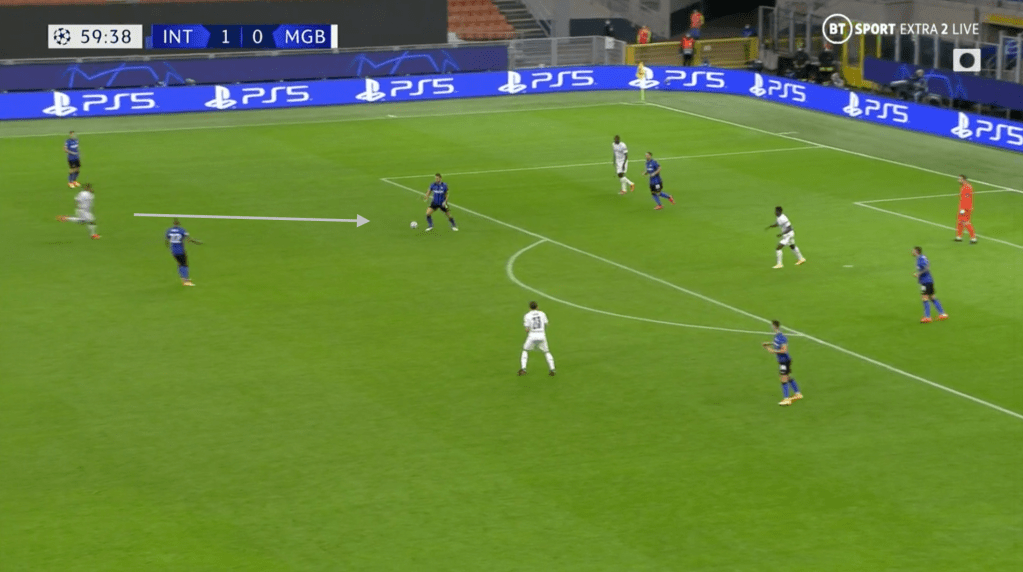

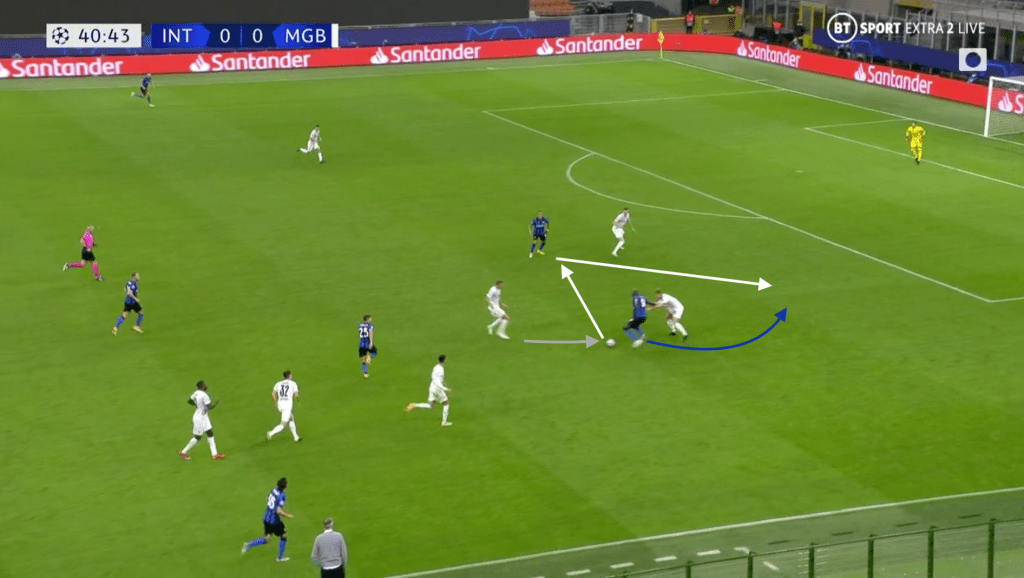

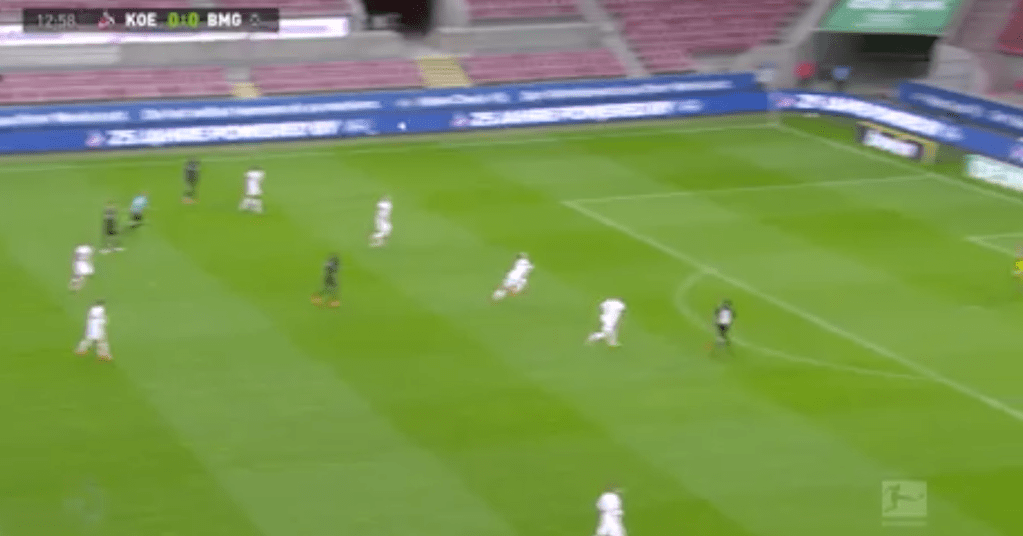

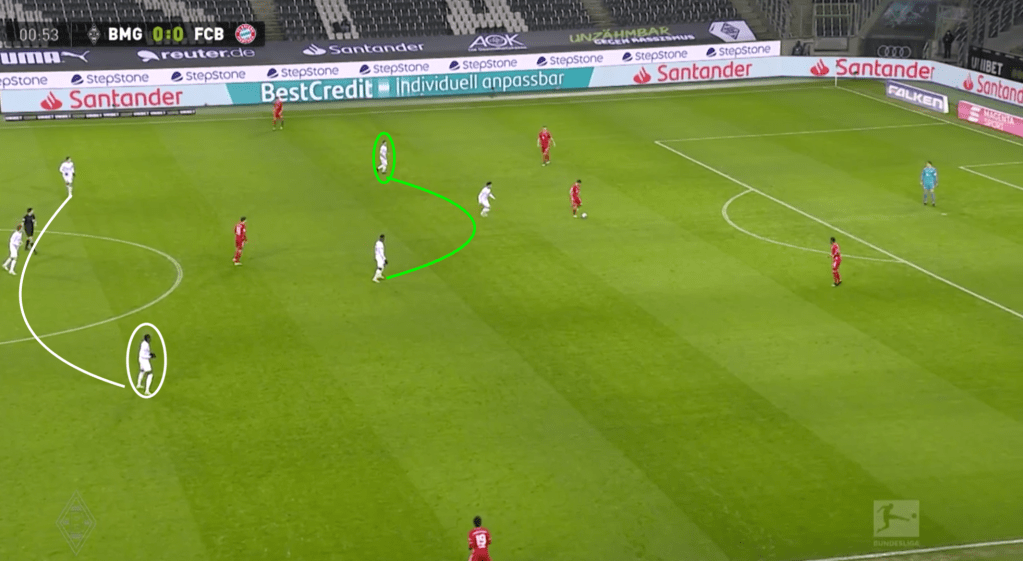

But it was not the case that it was one shape out of possession, and one shape in possession, because if Bayern played past the press and had the ball in the middle third, Hofmann quickly dropped back to form a bank of four with the rest of the midfield, as shown here, leaving Lars Stindl and Breel Embolo looking like a conventional front two.

This quirky set-up is facilitated by Hofmann’s pretty particular skill set. As Abel Meszaros puts it, he is expert at “backwards pressing”.

That means he can spend a lot of time positioned higher up the pitch, in the left-wing slot, and Gladbach still maintain a compact defensive shape, all thanks to his defensive work-rate.

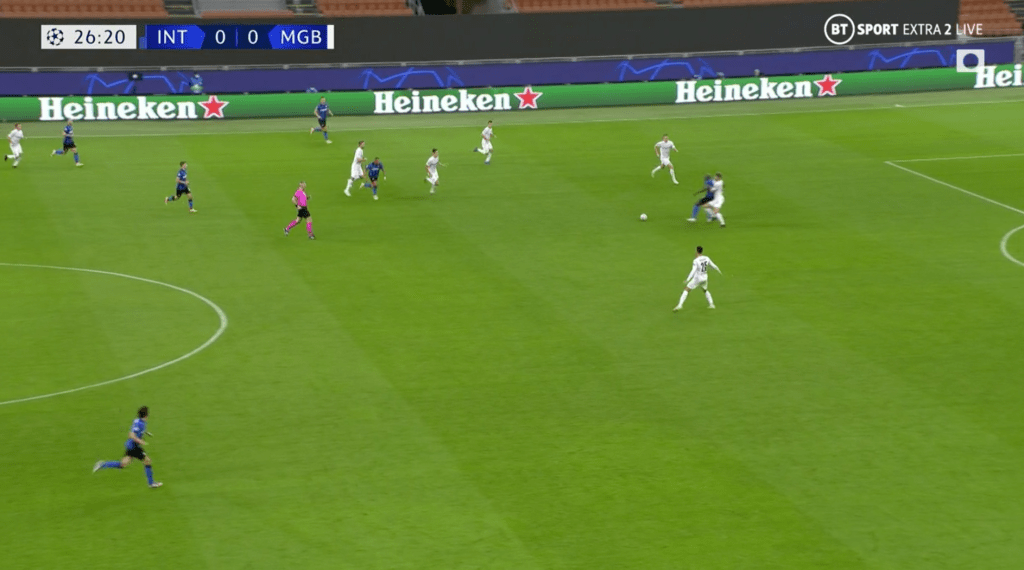

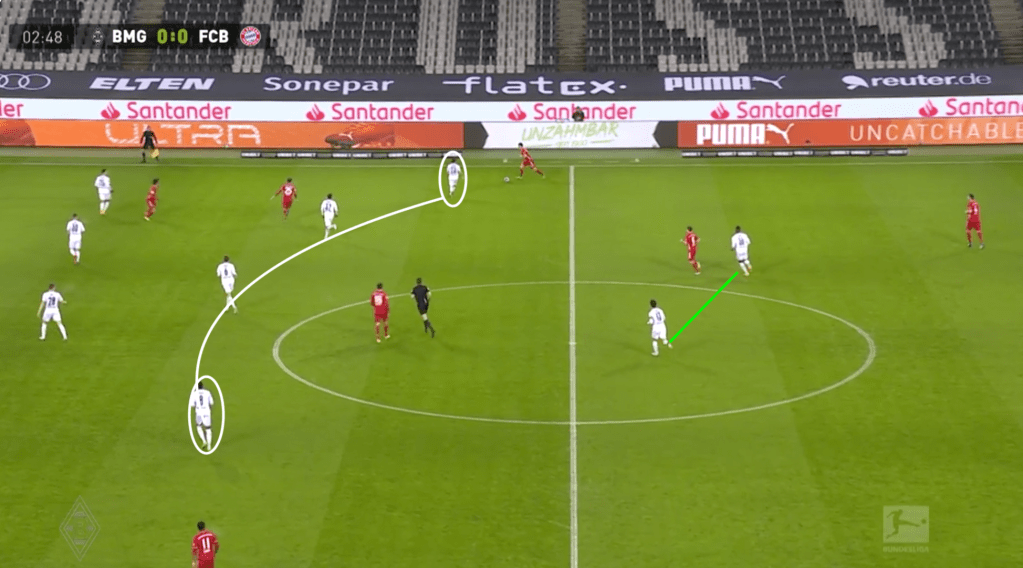

The purpose of this asymmetric system was to contain Bayern’s strengths and exploit their weaknesses. While forcing turnovers high up the pitch is one aim, a team with Bayern’s qualities will often find an out-ball, so channelling play is also important. Alphonso Davies at left-back has not been as explosive as last year, but poses much more of a threat than Benjamin Pavard at right-back, who was hooked at half-time against Mainz last week after an underwhelming showing. Joshua Kimmich often dropped back to split the centre-backs, meaning that Hofmann would also press up against Niklas Süle, a player much less comfortable on the ball than his defensive partner David Alaba.

Gladbach’s set-up did often leave space on their left flank, in behind Hofmann, and thus would leave Pavard free, at least for a moment. That made Pavard the more natural out-ball, compared to Davies, who always had Zakaria in front of him. Gladbach bet that by leaving Pavard free, they could channel play his direction. Of all Bayern’s players, he was the least likely to cause them problems, and even if he had a little time on the ball, it was never long, thanks to Hofmann’s backwards pressing.

That all seems a little complicated, given it results in the endpoint of Hofmann closing down Pavard. Why didn’t he just sit off in the bank of four, stand in front of Pavard, and close in down in a regular way? It would have certainly saved him some energy, but there are two good reasons.

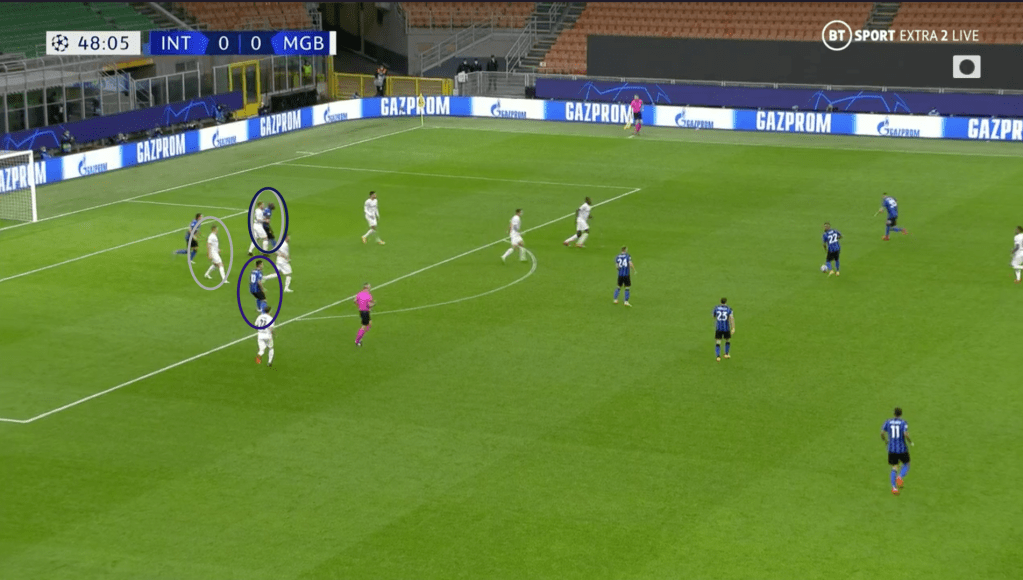

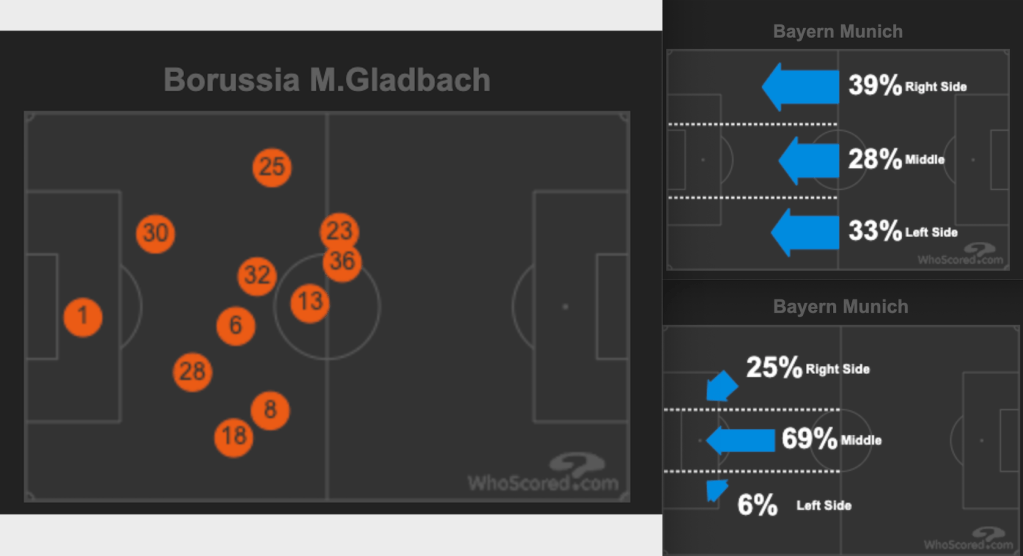

Firstly, unless Gladbach’s tactics forced the ball out towards Pavard, Bayern likely would have directed more play out towards Davies, and probably threatened more often from the left. As it was, Stevie Lainer (18) and Zakaria (8) were close together, and clogging up that flank, compared to Ramy Bensebaini (25), who, on the face of it, had to cover more space by himself (until Hofmann made up the ground to help out). As such, Bayern directed more play down the right, as you can see. (Thanks WhoScored for these graphics. Gladbach player’s average position is on the left. On the right, Bayern’s attack sides are on top, with shot directions on the bottom)

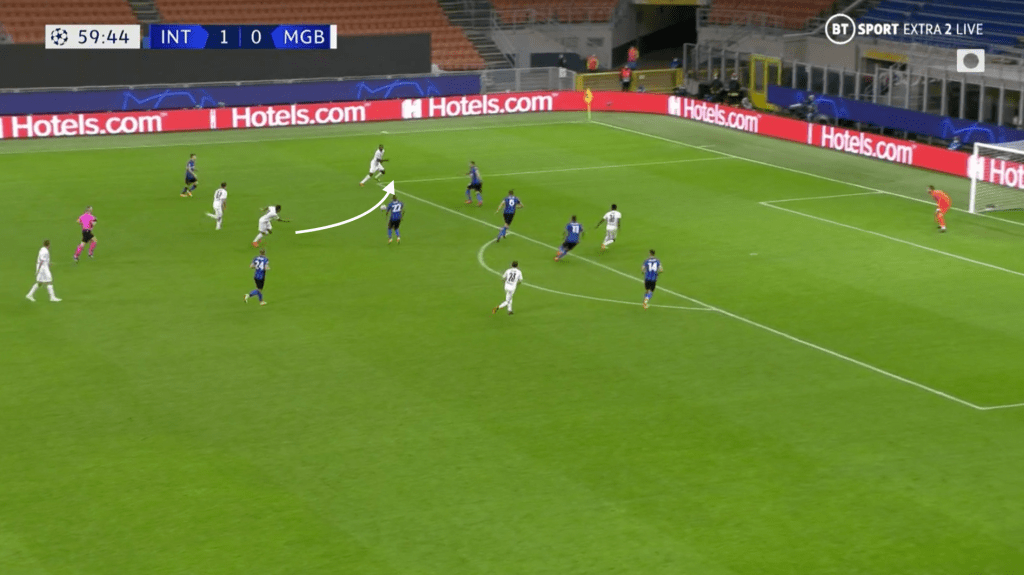

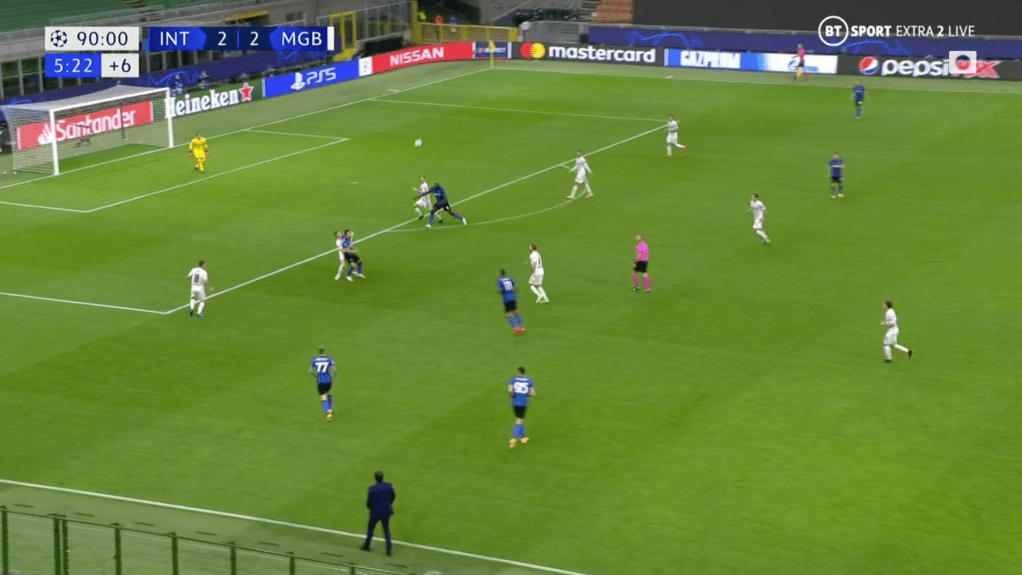

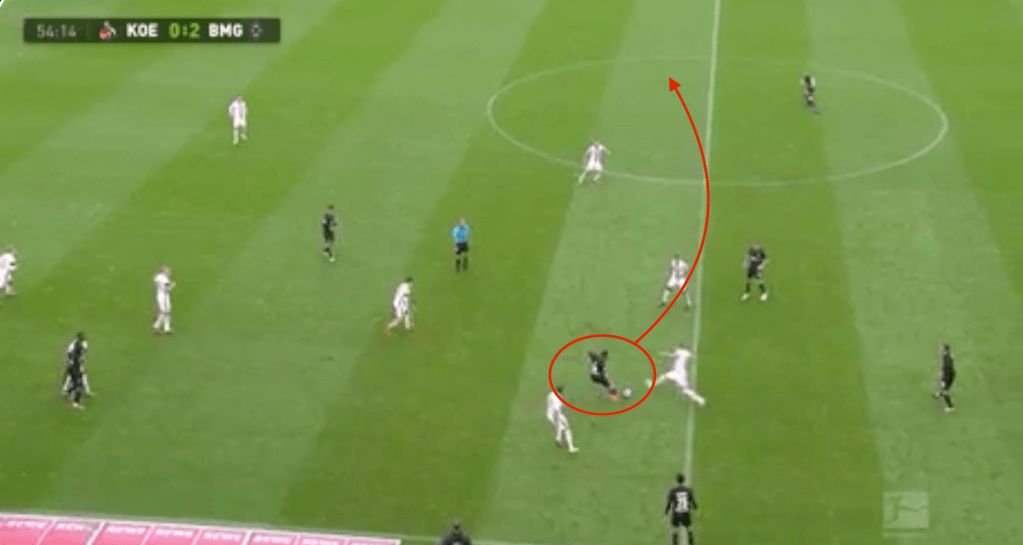

The second reason helps explain the comeback. We’ve focussed so far on the assumption that Bayern, as a good team, usually beat the press. But Gladbach tested them to the limit, and in positioning Hofmann high up, he was able to pick on the weak links of Pavard and Süle – not only to channel play into areas of relative safety, but to counterpunch. If his backwards pressing helped Gladbach keep their shape, it was his forwards pressing which led to Gladbach’s key breakthroughs.

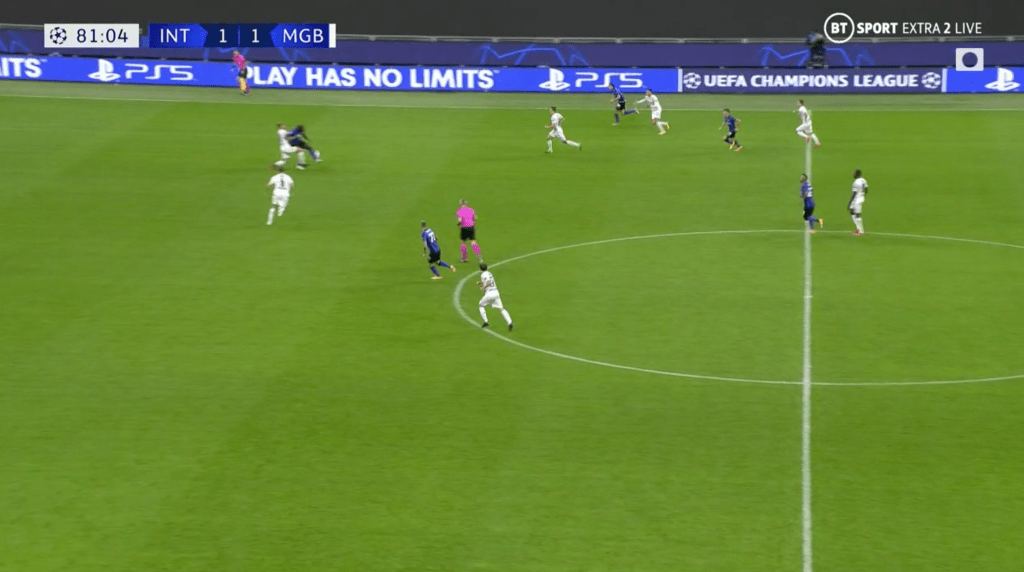

In the build up to the first goal, it’s worth considering what didn’t happen, as well as what did. Bayern did not build an attack from the left. Thirty seconds before Hofmann scores, Bayern are knocking it about the back and the ball is played to Davies. He is confronted with Zakaria, who contains him. He doesn’t dive in and give Davies the option of dribbling around him, and he doesn’t press overly aggressively. But Davies has nowhere to go but backwards.

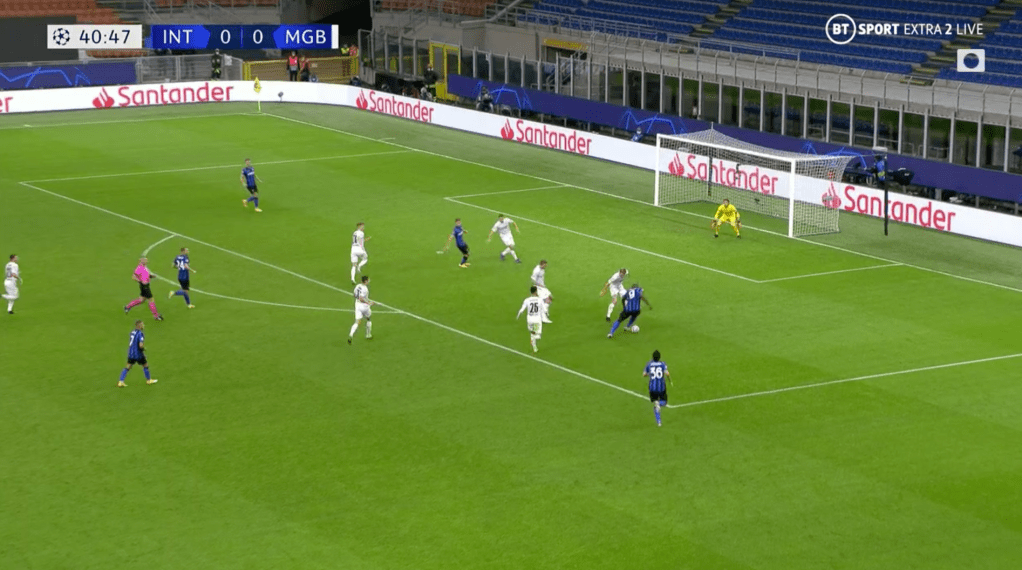

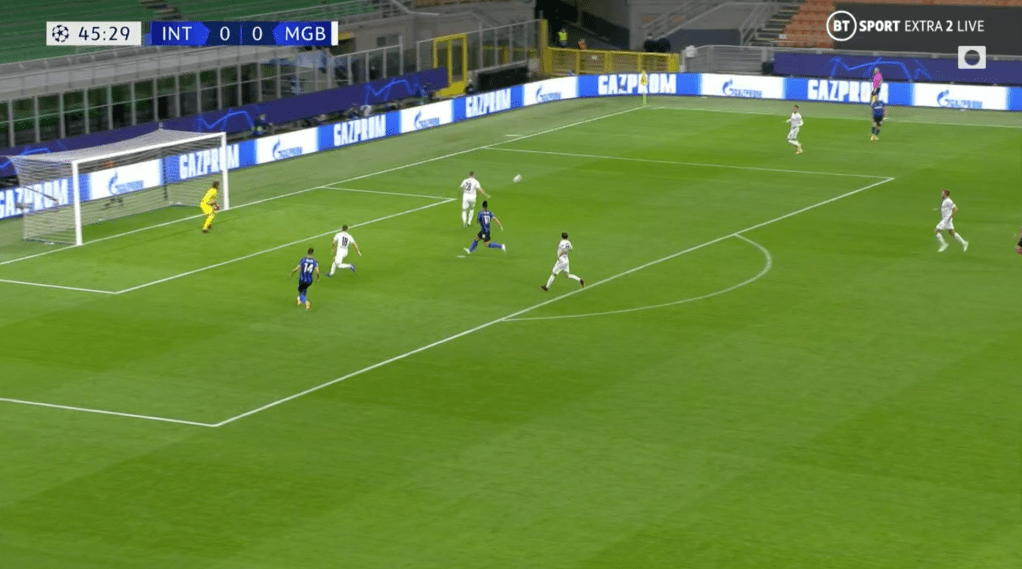

A few seconds later, the ball is worked to the other side. Kimmich hasn’t dropped in between the centrebacks, and so Hofmann can press directly onto Pavard. The trap is set. He goes in aggressively, knowing that Pavard is not going to dribble past him in the way Davies might.

Pavard instead chips a poor quality ball to Sane, and Bensebaini completes his part of the press, forcing a turnover. Hofmann then shows the other side of his game, working the ball well with Neuhaus and then getting on his bike to exploit the left channel, blazing past the flat-footed Süle, taking the lovely ball from Stindl and slotting home.

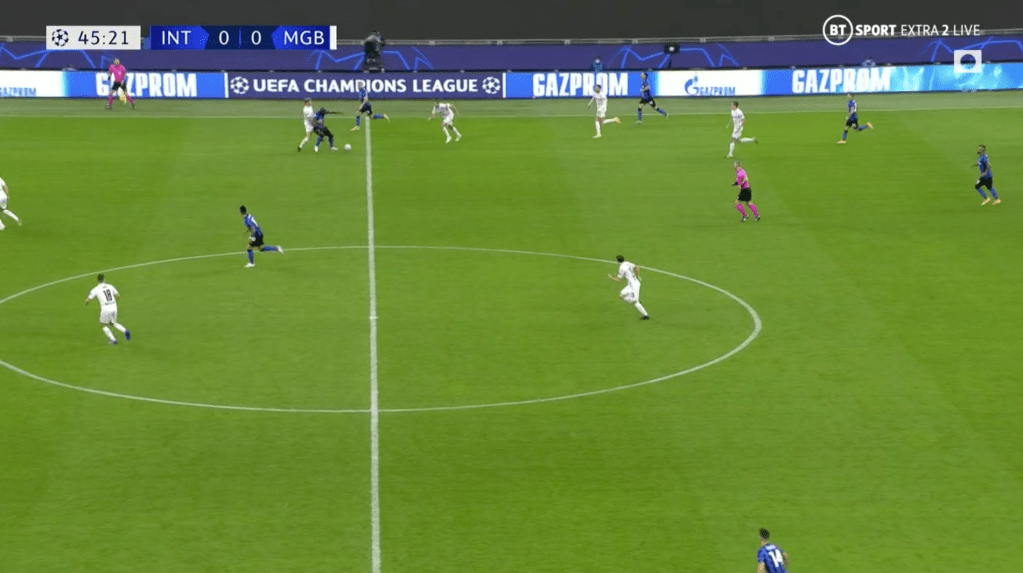

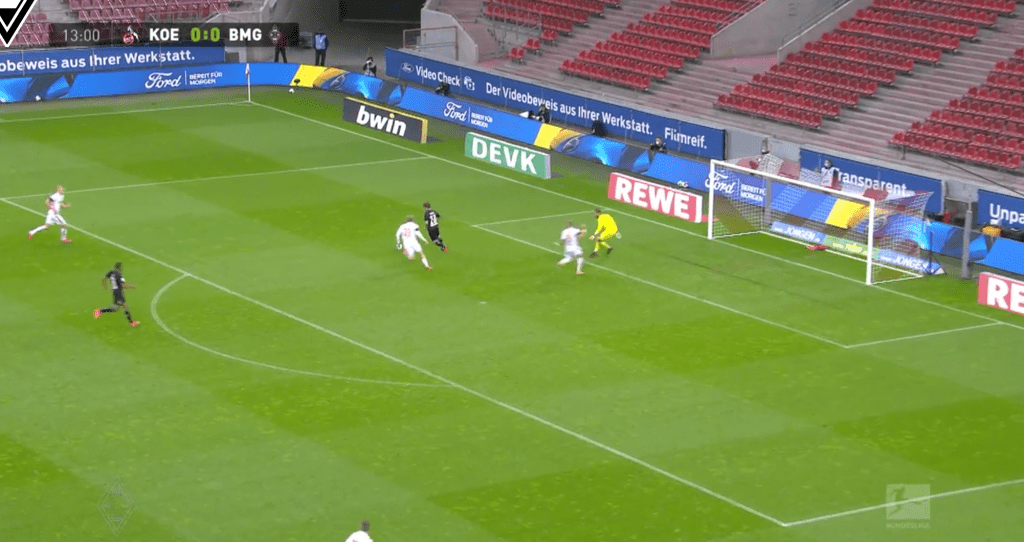

Ironically, Zakaria was right up there with Hofmann to sprint in on goal, but in general, he did not offer the attacking outlet Hofmann did, demonstrated clearly in the second goal, where Hofmann caught Süle flat-footed the other direction as the centre-back stepped up too slowly and the Gladbach man beat the offside trap to convert another one-on-one, assisted beautifully once more by Stindl.

For the third goal, again Bayern try and work it up the right. Again Hofmann presses aggressively, this time intercepting the pass from Süle to Pavard. Süle then fails to close Hofmann down on the edge of the box, and he slips in Neuhaus who curls home beautifully.

Aside from a freakish penalty for handball, which Gladbach’s own Twitter admin attributed to a Neuhaus “brain fart”, and a well taken long-range shot from Goretzka from Bayern’s own counterpunch, where an unsighted Sommer was caught cold, Bayern did not create much. Their best moments came from Gladbach’s own struggles playing out from the back, rather than Bayern’s success in building up attacks from deep. And though Bayern had 67% possession, Sommer had very little to do, and, taking out the bizarre penalty, an xG of only about 0.6.

Gladbach did not get many chances themselves, and had to take them when they came. That goes without saying when you face a world-class team like Bayern Munich. But the system that Marco Rose and his team came up with made sure to limited Bayern’s own chances, keep Gladbach compact, exploit Bayern’s weaknesses and counterpunch in a way that meant helped create relatively high quality openings for the team. Rose has now beaten Hansi Flick’s Bayern twice, and after failing to beat Dortmund, Leverkusen, Wolfsburg or Union Berlin, such a positive result against the best team in the country will hopefully reignite Gladbach’s challenge for the European places.